Through practices such as hiking, trekking or simply strolling, walking is in tune with the times. All steps? No. Contrary to other soft mobility, urban strolling, that of daily life, always summons the imagination of vulnerability, the banal and misery; far from the mental universe invoked by the walk of country getaway and strolling, from the mythology of the heroic and solitary hiker and his existential search for beauty and lost time. Between bad student and prodigal daughter mobilitywalking thus seems polarized between city and nature even as more and more city dwellers seek to reclaim it.

How, then, to re-enchant walking in the city ? What if the craze for leisure walking also made it possible to renew our perceptions of urban walking, by seeing it as a bodily technique and a social practice? Isn’t urban walking also an opportunity to transform our view of the city to better reinvent it? What if we upset the codes of walking in the city?

Walking between body technique and social practice

Walking is a biological mechanism, part of the infant’s natural evolution. But walking is also the result of a learning process, defined by an environment and which requires education specific to a given culture. For the sociologist Marcel Mauss, walking is even a “total social fact”, insofar as it condenses multiple social factors which vary from one society to another. Thus in New Zealand, Maori women teach their daughters to move to the rhythm of an extremely precise swaying of the hips, while in France it is the maintenance and uprightness of the body in motion that has long been the subject of he educational attention of the bourgeois and aristocratic classes: young girls, decked out with a pile of books placed on the top of their heads, have for centuries learned a codified way of walking, a symbolic guarantee of their social rank.

Much more than a biological determinism, walking is a technique of the body by which is incorporated a cultural capital to which one wishes to adhere, but which can also be the object of subversion.

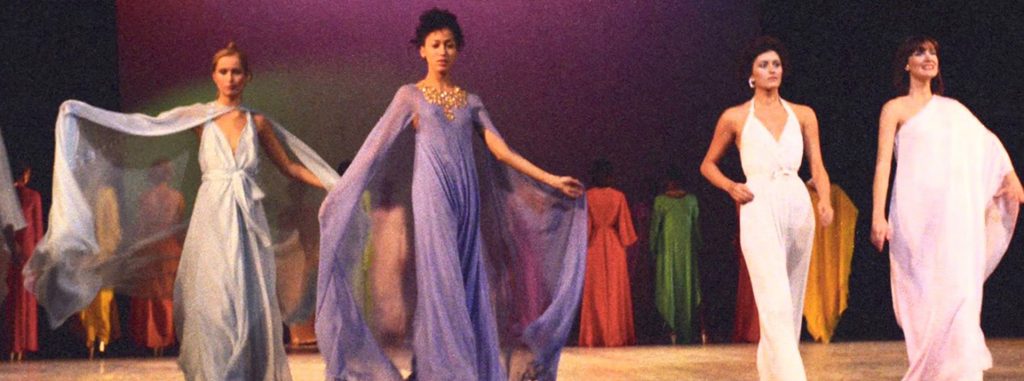

These techniques, which physically and socially shape the body, are also the subject of cultural appropriations for the purpose of social distinction: from colonial Morocco to contemporary China, learning this “French-style” walk, among others techniques of good manners, has been popular with the elites whose social imaginations are nourished by representations relating to the body by which they demonstrate their superiority. But the norm of good walking does not always spread from one culture to another. In the 1970s, the wandering techniques of fashion shows were the subject of an original appropriation through the rise of voguing: this swaying of the body, between walking and dancing, which emerged in the new clubs gay and transgender African-American Yorkers, consisted of overplaying the sophisticated approaches of the models. Here the appropriation and the diversion of a technique of the body aim, for groups which are socially distant from it, to parody the codes of the world of fashion and, consequently, of the white and American elite of the time. . So much more than a biological determinism, walking is above all a technique of the body through which is incorporated a cultural capital to which one wishes to adhere but which can also be the object of subversion.

But the social function of walking is not limited to sharing a technique of the body. Walking is also a social practice. The Parisian Sunday promenade at the Tuileries, in vogue at the end of the 19th century, was thus an equivalent of the social salons where the elite gathered for ostentatious purposes and sociological distinction. This social dimension of the march is not for all that the prerogative of the elites: the European working classes, the ethnic minorities have also invested the march with a socio-cultural function through the practice of the street demonstration which crystallizes its dimensions. civic and political. Finally, let us mention the religious dimension of walking: from centuries-old Christian pilgrimage routes to mass wanderings in Mecca, the movement of the body also appears as an individual and collective access route to the divine. Thereby, much more complex than it seems, walking is essential to the construction of social ties, in all its dimensions.

From walking to wandering: the master, the slave and the wanderer

On the other hand, walking receives a rather negative connotation when it is understood as a means of locomotion. Historically synonymous with slowness, even suffering – a suffering sometimes sought after as in Christian pilgrimages – walking was very quickly thought of as a constraint to be resolved in terms of human mobility. From then on, from the domestication of the horse to the invention of the wheel and then of the car, the introduction of modes of transport competing with walking will make the question of mobility a real issue of power in which the act of walking seems perpetually synonymous with weakness.

The cultural modalities of walking are at the heart of a struggle between domination and vulnerability.

Thus, the horse and the team remain globally, until the industrial revolution, class privileges to which the working classes have less access outside of an agrarian use. The latter’s strategies of distinction then take place via the possession of shoes which allow them to differentiate themselves from the marginalized who walked barefoot; hence the pejorative character of the expression “barefoot” to qualify the vagabond. Other marginalities are indicated by the absence, or rather the prohibition, of wearing shoes: the history of slavery and that of imprisonment are crossed by the obligation to walk without shoes, a sign of dehumanization. Similarly, women accused of witchcraft were forced to walk barefoot in order to neutralize their supposed powers. So many examples that demonstrate to what extent the cultural modalities of walking are at the heart of a struggle between domination and vulnerability.

The Industrial Revolution and the Sidestep of Walking

From the industrial revolution, motorization transformed the world of transport: so-called passive mobility became widespread while the practice of walking slipped towards sport and leisure through the birth of hiking and GR at the beginning of the Twentieth century. Walking as a daily means of locomotion is marginalized until it becomes the sign of anti-modernity; even though it has never ceased worldwide and still provided 60% of travel at the end of the 20th century.

The imaginary connection between walking and not owning a car was established during the Glorious Thirties and lasted until the 2000s. This representation increased as urban infrastructures developed around motorization. But, at the same time, out-of-town walking is a real craze in the West, around the hiking and trekking market. Between the two, remains the urban walk, in full ideological wandering, empty of any positive imagination. insofar as it refers to a universe spatially arranged for motorization; even though the improvement of walking conditions in the city is increasingly desired by the inhabitants of large cities for whom it evokes a way of life that would like to be closer to that of “village life”.

Accompanying the new imaginary of urban walking

Transport operators having understood the imperative to go beyond the sole logic of optimizing journey times for urban populations who increasingly prioritize their comfort, new initiatives are currently being put in place. However, from the speed limit to the suspended sidewalk, these advances only circumvent the problem of the balance of power between the pedestrian and the motorization.

Geolocation applications dedicated to urban mobility already offer walking as a mode of travel – alone or coupled with other modes of public transport – but without ever taking into account the specificity of this mobility.

Accompanying the trend towards urban walking cannot be conceived according to outdated mobility objectives such as that of the sole optimization of walking journey times. However, this is still mostly the case: geolocation applications dedicated to urban mobility already offer walking as a mode of travel – alone or coupled with other modes of public transport – but without ever taking into account the specificity of this mobility. . The elements that are likely to make an urban walking route a deleterious experience (pedestrian vulnerability to cars, unsuitable urban developments, neighborhoods to avoid, etc.) or, on the contrary, beneficial (width of the roadway, points of outstanding interests, etc.) are neglected.

Here, the margins for progress are immense and mobility operators would be wise to seize the desire – unprecedented in its scope – that urban dwellers manifest vis-à-vis walking in the city. There is a whole imagination here that needs to be helped to unfold to make this soft mobility a sensory and aesthetic experience in its own right, far from the uselessness or dangerousness with which the past has associated it.

An application optimized for urban walking, attentive to its physiological and emotional dimensions more than to travel times, could singularly encourage urban dwellers to walk “better”, in accordance with their expectations. Whether it is a temporally elastic stroll or a journey time that would be modulated by the philosophical or cultural experience that the user would seek to draw from it, such an application could encourage city dwellers to abandon marked routes. by infrastructures made for cars, to discover the crossroads unexplored by current applications and thus reclaim urban centers through poetic or historical peregrinations thematized and documented. The perspective seems all the more achievable since the city also offers daily micro-experiences of wandering and also summons imaginaries of lost time and space. At the beginning of the last century, the sociologist Georg Simmel wrote that the urban man is “a potential wanderer”. Once a negative figure, the wanderer has experienced a poetic rehabilitation through a mythology of hiking and existential wandering that can now extend to the territories of the city. The fields of inspiration are not lacking as walking is an object with multiple dimensions: from literature to philosophy, the movement of the walking body continues to accompany that of thought and imagination.

We would love to thank the writer of this write-up for this incredible material

Praise of walking, physical and social practice, to re-enchant the city

You can view our social media profiles here , as well as other pages related to them here.https://nimblespirit.com/related-pages/