Image courtesy of Flora Weil, Alexandra Smorodinova and Danya Orlovsky

[Sauf mention contraire, tous les liens de cet article renvoient vers des pages en anglais.]

In the early 1990s, Nicholas Negroponte, the founder of the MIT Media Lab, announced that the Internet “would disrupt organizations, globalize society, decentralize control, and help harmonize people.” Thirty years later, that prediction couldn’t be further from the truth. As the Internet has driven unprecedented globalization, innovation, and participation in previously inaccessible sectors, over the past two decades the slow and persistent efforts of governments around the world have made private technological achievement reign in regimes. regulatory and safety regulations.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine mark the next turning point compared to the international distributed and libertarian dreams of the 20th century Internet. The war accelerated three important trends in the geopolitical dynamics of the Internet, making any major reversal unimaginable. First, the war has accelerated the unprecedented importance of non-state actors in state-level warfare. Second, he highlighted the centrality of information networks in physical conflicts. Third, it has accelerated global fragmentation between the United States, Europe, Russia, and China along technology platforms.

At a United Nations conference in June, a Google executive predicted that Russian operations in Ukraine foreshadowed the new global status quo: “It’s basically our crystal ball for what’s likely to happen. »

The proliferation of non-state actors in state-level warfare

For most of modern history, warfare has been primarily the domain of nation states. Ivan Sigal argued that since the 1970s “there has been an increase in undeclared conflict, intra-state and civil conflict involving irregular combatants and non-state combatants, with fighting taking place in the midst of civilian life, where the majority of the victims are non-combatants”.

While non-state actors have taken part in past conflicts – the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) began during the Crimean War in the 1850s and modern terror is rooted in the anti-colonial rebellions of the 19th century – especially in the past 20 years, the presence of NGOs, international organizations and terrorist groups has begun to usurp the state’s monopoly on violence. Joseph Nye and Robert Keohane described this emerging world of international relations as that of a “complex interdependence”.

Interdependent, because during the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Mali, the States waged national wars against armed self-governing organizationsmonitored by a motley array of independent observers and supported in the periphery in peace efforts by hundreds of NGOs. Complex, because the boundary between aggressor and peacemaker has blurred. The Internet has made global conflicts even more anarchically complex and interrelated, due to the unprecedented range of interventions available.

Even before Russia invaded Ukraine, a decentralized community of researchers sounded the alarm about the abnormal movement of Russian troops along the Ukrainian borders. The proliferation of satellites, social media, public flight records and mapping techniques has made available a range of open source reporting methods capable of identifying war patterns before the shots are actually fired.

The growing interdependence of global networks and unrestricted access to them from anywhere in the world also means that one can wage war in Eastern Europe from an apartment in Berlin or a café in Shenzhen. . In February, the Government of Ukraine issued a global appeal to hacking groups to obtain aid in the defense of critical infrastructures. Since then, an unidentified group of pirate vigilantes has been disrupting the Russian news channels, government websites and military supply networks. Simultaneously, unidentified hacking groups started to increasingly target “NATO State Foreign Ministries, Humanitarian Organizations, Think Tanks, IT Groups and Energy Suppliers”. Western intelligence agencies have attributed these attacks to Russian state-backed groups, but the nature of the internet makes final attribution impossible.

Finally, war has given new meaning to technology platforms. Microsoft’s Seattle-based Threat Intelligence Center managed to prevent crippling attacks on Kyiv’s military and government networks. Google and Meta banned Russian media, defending against Moscow’s major influence operation abroad and giving prominence to Ukrainian voices. An American facial recognition company, Clearview AI, donated his software to the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense in order to identify the dead soldiers.

As tech platforms face anti-trust lawsuits in Europe and the United States, the war in Ukraine has served as a practical new argument against new anti-trust measures: harming tech platforms would help Russian propaganda.

The growing importance of networking technologies

Telecommunications have been a vital part of military operations since World War I. The development of the Internet itself was justified in the 1960s as a necessary precaution to maintain communication during a nuclear war. But throughout the past decade, singular moments have highlighted the emerging importance of cloud connections to physical realities. Unfreedom Monitor from Global Voices describes the unprecedented emergence of internet censorship efforts around the world.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 is the most recent, and perhaps most stark, example of the militarization of the internet in physical conquest.

The day before the entry of Russian troops into Ukraine, the modems of the satellite Internet network, Viasat’s KA-SAT, have been mass deactivated. Auxiliary Cyberattacks on Government Websites and Infrastructure Operators tried in vain to paralyze the command and control centers of Ukraine.

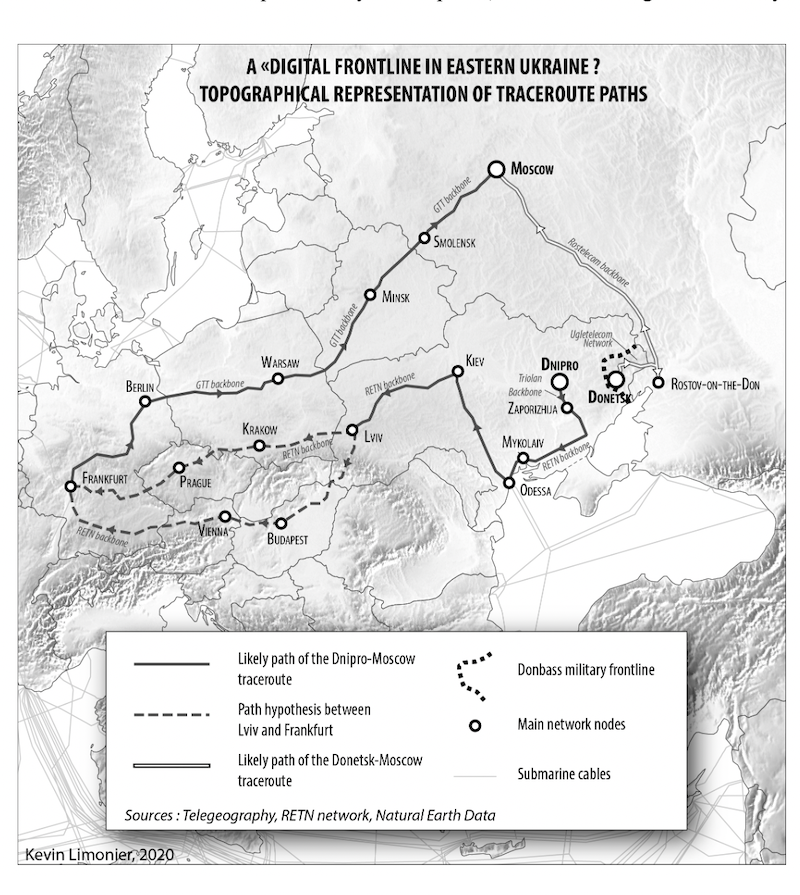

Overall, the war in Ukraine is the latest example in which control of telecommunications has both directed military movements and served as justification for annexation. In 2015, before the annexation of Crimea, Russian forces occupied the main offices of the ISPs of the peninsulacut all connections with Ukraine, built a new fiber optic submarine cable and redirected internet traffic through Moscow-based Miranda Media. This ensured that local internet traffic would be monitored by Roskomnadzor, Russia’s telecommunications regulator, and subjected Crimean residents to Russian speech, publication and internet regulations.

Map reproduced with the kind permission of Kevin Limonier.

Moscow follows the same scenario on an unprecedented scale in the newly occupied territories. ISP offices in Kherson and newly occupied towns in eastern Ukraine were also redirected to Russian networks, ensuring Russian informational control over the regions and laying the groundwork for future referendums on secession. It became a big enough concern that Ukrainians destroy telecommunications infrastructure as they flee occupied cities.

Security and control of national telecommunications channels becomes especially vital for smaller countries that rely primarily on foreign service providers for key military intelligence like satellite imagery. Volodymyr Usovformer Chairman of the National Space Agency of Ukraine, highlighted in June “Each nation that claims to be independent…must have its own constellation [d’imagerie] “. Usov noted that partnerships are not enough: “you need to have stand-alone access to satellite imagery.” Ukraine plans to develop its own satellite launch technology to protect vital communications infrastructure from field operations.

Rapid geopolitical fragmentation along infrastructure

The involvement of non-state actors and the growing military importance of telecommunications are leading to an accelerated balkanization of the Internet along national lines.

The war in Ukraine has drawn an even more explicit curtain between national Internet regimes. Thanks to an unpleasant fuss, Russia has banned the majority of Western tech companies and media. Simultaneously, Ukraine and the West banned Russian public media sites. Moscow attempted to ban TOR and VPN networks, which have the ability to circumvent government censors. In a final extension of Internet sovereignty, Russia has sought to prosecute its citizens for posting negative statements about the war, even if they live abroad. National boundaries no longer stop at the border, but now extend into media spheres of any geography with an internet connection.

The war in Ukraine drew a more explicit line between the fragmented financial, informational, and infrastructural realities of Europe and the United States, set against Russia and China. A non-aligned infrastructural movement is on the way, unfolding according to the sclerotic logic of the Cold War. In the 21st century, the choice for much of the world is not communism or capitalism, but rather the supply chain network that their countries will tap into.

Image courtesy of Giovana Fleck.

For more on this topic, check out our special coverage on The Russian Invasion in Ukraine.

We want to give thanks to the writer of this article for this outstanding web content

The war in Ukraine fundamentally changes the relationship between the Internet and geopolitics

You can find our social media profiles as well as other related pageshttps://nimblespirit.com/related-pages/