We are in Rome, in 1960. On the facades of the buildings under construction, a strange shadow emerges, that of a statue of Christ transported by helicopter from the via Appia Antica to the Vatican. From the rooftops, women in bikinis greet her. This scene opens the Dolce Vita by Federico Fellini. A sculpture freed from its pedestal, a religious symbol turned into an advertising plane banner, a shadow theater projected over a city preparing for the years of lead: this Fellini sequence could very well serve as a flashlight to illuminate the labyrinth. of the’arte poverathis Italian artistic avant-garde movement of the 1960s. Rejecting the didacticism of academic art and challenging the popular cultural industry, the artists of thearte povera moved the work of art from artifact to process, from museum to life, creating improbable images in a great economy of means.

“They create icons while freeing themselves from the rhetoric of the icon, explains Giuliano Sergio, one of the curators of the exhibition devoted to I’arte povera 1960s to 1975 which is currently being held in Paris, at the Jeu de Paume museum and at the Bal. They free themselves from ideological discourse, but without losing this history that feeds them; it’s their way of looking towards modernity“. How to grasp all the richness of this poor art ? Here is a gateway to the great constellation of this protest utopia of the late 1960s, which was perhaps at that time one of the most original reactions of the European avant-gardes to the hegemony of art. American contemporary on the art market.

An Italian and radical art

In terms of taxonomy, art history probably isn’t the best humanities student, especially when it delegates to critics the responsibility of naming a movement. Whether cubism and fauvism were born out of the mockery of a rather conservative art critic, thearte povera was very seriously defined by Germano Celant, in 1967, in a manifesto. It accompanied the exhibition “Arte povera-IM spazio”, organized in a gallery in Genoa, with a dozen artists – the unofficial list of current members: Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Giulio Paolino, Pino Pascali, Emilio Prini, Giovanni Anselmo, Paolo Calzolari, Luciano Fabro, Mario and Marisa Merz, Giuseppe Penone, Michelangelo Pistoletto and Gilberto Zorio… Most of them work from primary materials (wool for Kounellis, straw for Pascali or wood for Penone), which they enrich with a poetic dimension or show us in their raw materiality, for what they are and not what they represent. But make no mistake, “the poverty of a material for arte povera is rather the idea that the essential is linked to the gesture, precise Diane Dufour, Director of the Ball, on France Culture. It’s a gesture that guides, that encapsulates a lot of intentions, emotions or perceptions, while remaining simple.”

At that time, Italy was emerging from the post-war economic miracle, people were dancing to the sound of American singers, but the air was red in the background. The student revolt of 1968 met that of the workers the following year, before giving way to the black chapter of terrorism of the “years of lead”. In the field of art, Lucio Fontana has opened with a cutter the breach of a questioning of the traditional practice of painting. The young artists of thearte povera engulfed themselves in it, subverting the classic functions of artistic mediums, distinguishing themselves both from informal art and its mute poetics, and from pop art and its mercantile chatter which then reigned over the art market. Taking the opposite view of the glorification of industrial culture and triumphant pop art, against the enthusiasm for technology, advertising and the new media, the poverist artists developed new aesthetic and political strategies: a work purified in its gesture and its materials, a local anchoring of the works, and more broadly, a reflection on the place of man in the nature/culture dichotomy.

listen later

59 mins

If the plastic gesture is intended to be radical and innovative, many Poverist works carry the memory of the history of Italian art, as evidenced by the photographs of Luigi Ontani disguised as Dante (picture above) or installation Venere degli stracci (1967) by Michelangelo Pistoletto, encounter between an immaculate Venus and a pile of multicolored rags. “Arte povera artists maintain a more peaceful relationship with their history and heritage than other European avant-gardes of the 1960s“, emphasizes Quentin Bajac, director of the Jeu de Paume museum.

A dialogue that also takes place with current events, with history in the making. In the troubled context of the 1960s and 1970s, marked by the contestation of social movements, massive strikes and terrorism, artists took over the city, gave birth to their works by involving the population. Mario Cresci thus wants to go out “the photograph of its frame – that of the image and of the studio” describes Quentin Bajac, by producing large photographic rolls of the demonstration of the victims of the earthquake which occurred in Sicily in 1968 against the inaction of the public authorities. The same year, Cresci conceives another photographic roll which he deploys in the streets of Rome to challenge passers-by on police violence and the threat of nationalism; a happening quickly interrupted by the police.

listen later

59 mins

Michelangelo Pistoletto, meanwhile, rolls under the famous arcades of Turin a large ball of newspapers called “Spiny World Map”, before presenting it in a gallery enclosed in a cage; once the intervention is over, the work of art in the museum becomes an object again. We should also mention Franco Vaccari, who decided to provide passers-by with a photo booth so that, as spectators-actors, they can take their portraits and pin their own photographs in the exhibition space (picture above). While subverting the places of art, these artists drew a portrait of Italy at the rhythm of its social and political upheavals.

listen later

51 mins

Art as experience, life as theater

![Understand the richness of arte povera in a few works 6 Giulio Paolini Antologia (26/1/1974) [Anthologie (26/1/1974)]1974 Invitation cards inserted between two canvases mounted one against the other.](https://nimblespirit.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1666041340_507_Understand-the-richness-of-arte-povera-in-a-few-works.jpg)

Although these Italian artists are part of a form of resistance to contemporary art from across the Atlantic, a very American reference hovers above their work: that of the philosopher John Deweyauthor of Art as experience (1934). This work translated into Italian in 1951 will have a strong impact in artistic circles. Reconciling pragmatism and aesthetics, Dewey defines the human being as a “to be in relation“with his environment, a being capable of infusing the parcels of the visible world with a value and a meaning that transcends them and returns to the invisible world of emotions, desires, dreams… In this sense, aesthetics is not radically distinguished other forms of human experience, “aesthetics are not added to the experience, from the outside, whether in the form of idle luxury or transcendent ideality“, writes Dewey, but constantly underlies our relationship to what surrounds us.

listen later

28 mins

“They will thus take over life with this idea that life must integrate art and that art must integrate life”. points out Diane Dufour. This decompartmentalization of arts and life, or of imagination and reality, is expressed among these Italian avant-garde artists in different ways. Some, mentioned above, create works that take shape in the street, put the artistic medium at the service of unvarnished social and political imagery. Others, like Luigi Ontani, explore their identity as lived, traversed by art: “I chose to make my painting life, and my painting performance, not to experience oblivion, but to resuscitate the history of art, fable, mythology, allegory, folklore, iconology“, will explain the artist who, in his self-portraits drawn in the heart of the years of lead, revived mythical Italian figures.

![Understand the richness of arte povera in a few works 8 Laura Grisi The Measuring of Time [La mesure du temps]1969 16 mm film (still), black and white, sound, 5 min and 45 s, Courtesy Estate Laura Grisi.](https://nimblespirit.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1666041340_412_Understand-the-richness-of-arte-povera-in-a-few-works.jpg)

But it is perhaps above all through performance that these Poverist artists will put into practice this relationship between art and life. Through a more experimental practice, they express a new relationship to art, in which the artistic process is just as – if not more – important than the work, the action than the object, the gesture than the image. One then thinks of another European avant-garde movement which is contemporary to it: Fluxus, whose spirit could be summed up by Robert Filliou’s letter “Art is what makes life more interesting than art“.

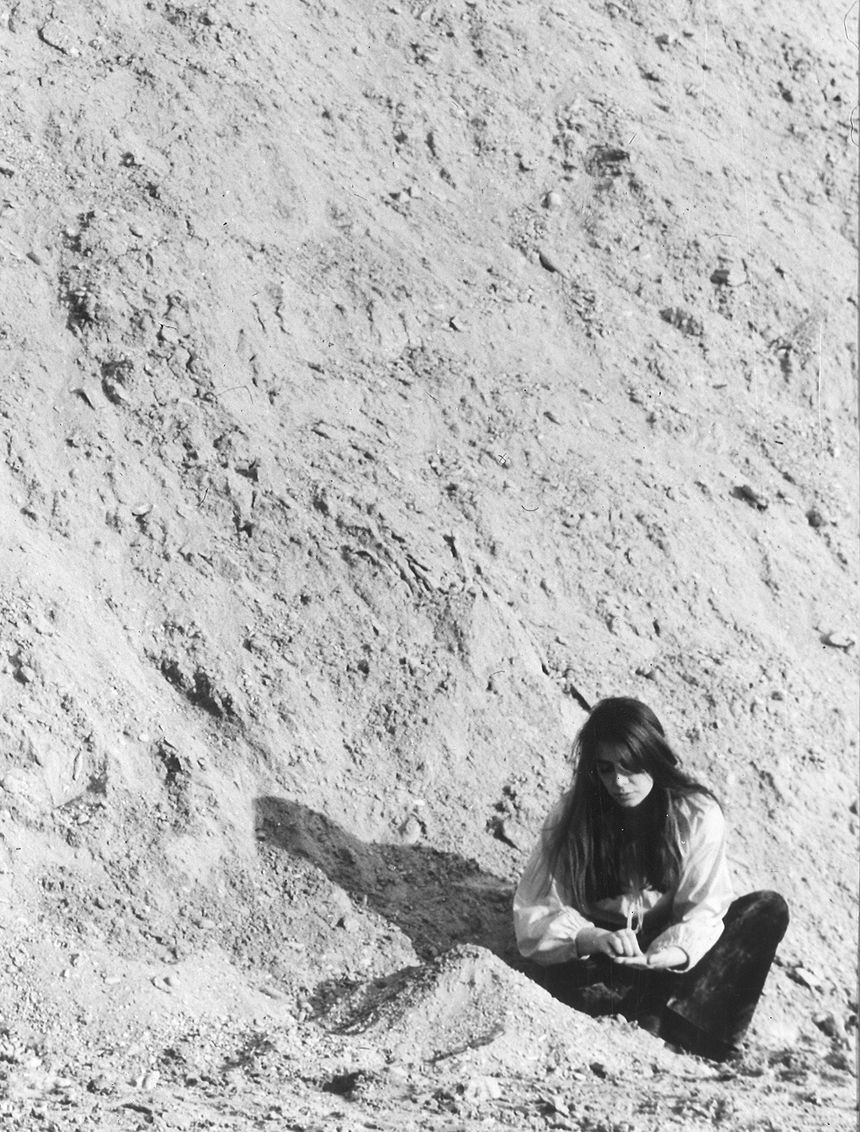

The performances of the poverists then differ from those of the neo-dadaists in that they touch us by their sobriety, their poetics often nourished by a reflection on the place of the human in relation to nature. It is for example this vain measure of time operated by Laura Grisi in 1969: a black and white film of five minutes, where we see the artist at the crossroads ofarte povera and land art count the grains of sand on a beach, slowly, in the palm of your hand (picture above).

It’s still that “attempt to form squares instead of circles around a pebble thrown into the water” (picture above), a work from 1969 which is almost entirely in its process, like the image in its title. “The artist seated at the edge of a pond makes circles in the water with a stone, with the only difference that his effort tends to create squares in the watercomments the director of Jeu de Paume. We find a form of absurdity by which the artist defies the laws of physics and seems to impose a rational order on the natural world which ignores it.“. We then think of theVitruvian man drawn by Leonardo da Vinci, a square man forced into a circle by the forceps of mathematical rationality… and the Pové artist to reverse perception, reminding us with a humble pebble of this natural resistance, the impossible squaring of the circle.

listen later

7 mins

We wish to thank the author of this short article for this incredible content

Understand the richness of arte povera in a few works

Check out our social media profiles and other related pageshttps://nimblespirit.com/related-pages/