Agnès Bastit pays tribute to the writer and literary critic Patrick Kéchichian, who has just died at the age of 71. Converted to Catholicism thanks to Cardinal Lustiger, he gracefully expressed the luminous art of praise.

The writer Patrick Kéchichian, a long-time literary critic at the newspaper The world and columnist at The cross, died on October 18. He was the son of Armenian emigrants. Around his thirties, he discovered and embraced Catholicism thanks to the charism of Bishop Lustiger who gave him the sacrament of Confirmation. Since then, while continuing his activity as a writer (The Midnight Needle, Princes and Principalities, Disfavour) and criticism, which for him was an exercise in openness to others, he retained the humility and wonder of the convert in the face of the Catholic faith. He knew how to express it with grace in a short and luminous text, his A short eulogy to Catholicism (Gallimard, 2009) followed, in the same spirit of highlighting Christian literature, by a commented anthology of Pauline texts: Saint Paul, the genius of ChristianityLittle Wisdoms, 2012.

Praise of Catholicism

In memory of this beautiful poetic and Christian voice, let us read a few lines taken from his A short eulogy to Catholicism (Gallimard):

“The desire for praise, like all true desire, is outgoing, joyful abandonment of self. He invents his language. Singular, it is neither natural nor spontaneous, but exclamatory, poetic, prayerful, gushing… Even poor and awkward…, it is still rich, not from itself, but from what makes it incessantly spurt out… Praise supposes the existence, the consistency of the person (or of the thing) whose merits, interest, intelligence, beauty, height, depth, etc., we want to say and sing. You must first name this person — or fail to name him — invoke him, place oneself in thought… in front of him. »

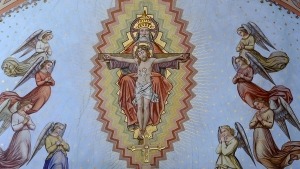

A few notes in the margin of this rich text. First of all, praise or acclamation is “ex-clamative”, in the sense of leaving oneself, of exploding out of interiority and turned towards others. Its (relative) poverty comes from the fact that it is not a question of a composed, mastered discourse, but of the repetitive bursting overflowing from the heart of the faithful. The praise then becomes deliberately accumulative, like the repeated cry of the sanctus (“holy, holy, holy”) or like the avalanche of synonyms that crowd into the Gloria “we praise you, we bless you, we adore you, we give you thanks…”). The precision of the adverb “incessantly” echoes the advice of Paul, the beloved master of Patrick Kéchichian “incessantly give thanks” (1 Thess 5, 17-18). One still thinks of the praise of the Seraphim, whose liturgy tells us that they launch their cry with an incessant voice (“ incessabili voce proclaiming“, according to the anthem of the Te Deum). Therefore, praise is by nature “poetic”, that is to say that the richness of its object gives it a beauty of form – the form of the hymn or the psalm – which does not come from a simple human primer.

“Wherever man touches divine things, his tongue departs from common language, his tongue is sanctified, so to speak, by contact with the divine”

The fundamental dimension of praise

As the great specialist in ancient Christianity and liturgical language Christine Mohrmann once wrote, “Wherever man touches divine things, his language departs from common language, his language is sanctified, so to speak, by contact with the divine”. Then comes the fundamental dimension of praise: its orientation towards a being external to us, which calls for praise precisely by what is praise — its greatness, its goodness, its beauty, etc. The fact of “naming” corresponds to the culmination and the final stage of the process, the one that finally makes it possible to reach the person targeted, to enter into a relationship with him, to initiate a “face to face”.

Everything therefore happens as if this could only happen after a suspensive stoppage, making perceptible the distance, the necessary effort, sometimes marked by impotence, to reach the object of his praise. The cry of the Seraphim reported by Isaiah thus ends, after the triple repetition of the affirmation “holy”, in pronouncing the name of the one whose holiness is proclaimed: “holy – Lord Sabaoth“. Before sinking into the contemplation of the face of this Lord. This is the lesson in praise given to us by Patrick Kéchichian, for which we are grateful to him.

We want to thank the writer of this post for this outstanding web content

The art of praise in the convert Patrick Kéchichian

Explore our social media profiles and other pages related to themhttps://nimblespirit.com/related-pages/